Prioritizing: The Wisdom of Knowing What to Overlook

By John C. Maxwell

Excerpt from Leadership 101

You Cannot Overestimate the Unimportance of Practically Everything

I love this principle. It’s a little exaggerated but needs to be said. William James said that the art of being wise is “the art of knowing what to overlook.” The petty and the mundane steal much of our time. Too many are living for the wrong things.

Dr. Anthony Campolo tells about a sociological study in which fifty people over the age of ninety-five were asked one question: “If you could live your life over again, what would you do differently?” It was an open-ended question, and a multiplicity of answers came from these eldest of senior citizens. However, three answers constantly reemerged and dominated the results of the study. Those answers were:

- If I had it to do over again, I would reflect more.

- If I had it to do over again, I would risk more.

- If I had it to do over again, I would do more things that would live on after I am dead.

A young concert violinist was asked the secret of her success. She replied, “Planned neglect.” Then she explained, “When I was in school, there were many things that demanded my time. When I went to my room after breakfast, I made my bed, straightened the room, dusted the floor, and did whatever else came to my attention. Then I hurried to my violin practice. I found I wasn’t progressing as I thought I should, so I reversed things. Until my practice period was completed, I deliberately neglected everything else. That program of planned neglect, I believe, accounts for my success.”

The Good is the Enemy of the Best

Most people can prioritize when faced with right or wrong issues. The challenge arises when we faced with two good choices. Now what should we do? What if both choices fall comfortably into the requirements, return, and reward of our work?

How to Break the Tie Between Two Good Options

- Ask your overseer or coworkers their preference.

- Can one of the options be handled by someone else? If so, pass it on and work on the one only you can do.

- Which option would be of more benefit to the customer? Too many times we are like the merchant who was so intent on trying to keep the store clean that he would never unlock the front door. The real reason for running the store is to have customers come in, not to clean it up!

- Make your decision based on the purpose of the organization.

Too Many Priorities Paralyze Us

Every one of us has looked at our desks filled with memos and papers, heard the phone ringing, and watched the door open all at the same time! Remember the “frozen feeling” that came over you?

William H. Hinson tells us why animal trainers carry a stool when they go into a cage of lions. They have their whips, of course, and their pistols are at their sides. But invariably they also carry a stool. Hinson says it is the most important tool of the trainer. He holds the stool by the back and thrusts the legs toward the face of the wild animal. Those who know maintain that the animal tries to focus on all four legs at once. In the attempt to focus on all four, a kind of paralysis overwhelms the animal, and it becomes tame, weak, and disabled because its attention is fragmented. (Now we will have more empathy for the lions.)

If you are overloaded with work, list the priorities on a separate sheet of paper before you take it to your boss and see what he will choose as the priorities.

The last of each month I plan and lay out my priorities for the next month. I sit down with my assistant and have her place those projects on the calendar. She handles hundreds of things for me on a monthly basis. However, when something is of High Importance/High Urgency, I communicate that to her so it will be placed above other things.

All true leaders have learned to say no the good in order to say yes to the best.

When Little Priorities Demand Too Much of Us, Big Problems Arise

Robert J. Mckain said, “The reason most major goals are not achieved is that we spend our time doing second things first.”

Often the little things in life trip us up. A tragic example is an Eastern Airlines jumbo jet that crashed in the Everglades of Florida. The plane was the now-famous Flight 401, bound from New York to Miami with a heavy load of holiday passengers. As the plane approached the Miami airport for its landing, the light that indicates proper deployment of the landing gear failed to light. The plane flew in a large, looping circle over the swamps of the Everglades while the cockpit crew checked to see if the gear actually had not deployed, or if instead the bulb in the signal light was defective.

When the flight engineer tried to remove the light bulb, it wouldn’t budge, and the other members of the crew tried to help him. As they struggled with the bulb, no one noticed that their aircraft was already dangerously losing altitude, and the plane simply flew right into the swamp. Dozens of people were killed in the crash. While an experienced crew of high-priced pilots fiddled with a seventy-five cent light bulb, the plane with its passengers flew right into the ground.

Time Deadlines and Emergencies Force Us to Prioritize

We find this in Parkinson’s Law: If you have only one letter to write, it will take all day to do it. If you have twenty letters to write, you’ll get them done in one day. When is our most efficient time in our work? The week before vacation! Why can’t we always run our lives the way we do the week before we leave the office, making decisions, cleaning off the desk, returning calls? Under normal conditions, we are efficient (doing things right). When time pressure mounts or emergencies arise, we become effective (doing the right things). Efficiency is the foundation for survival. Effectiveness is the foundation of success.

On the night of April 14, 1912, the great ocean liner, the Titanic, crashed into an iceberg in the Atlantic and sank, causing great loss of life. One of the most curious stories to come from the disaster was of a woman who had a place in on of the lifeboats.

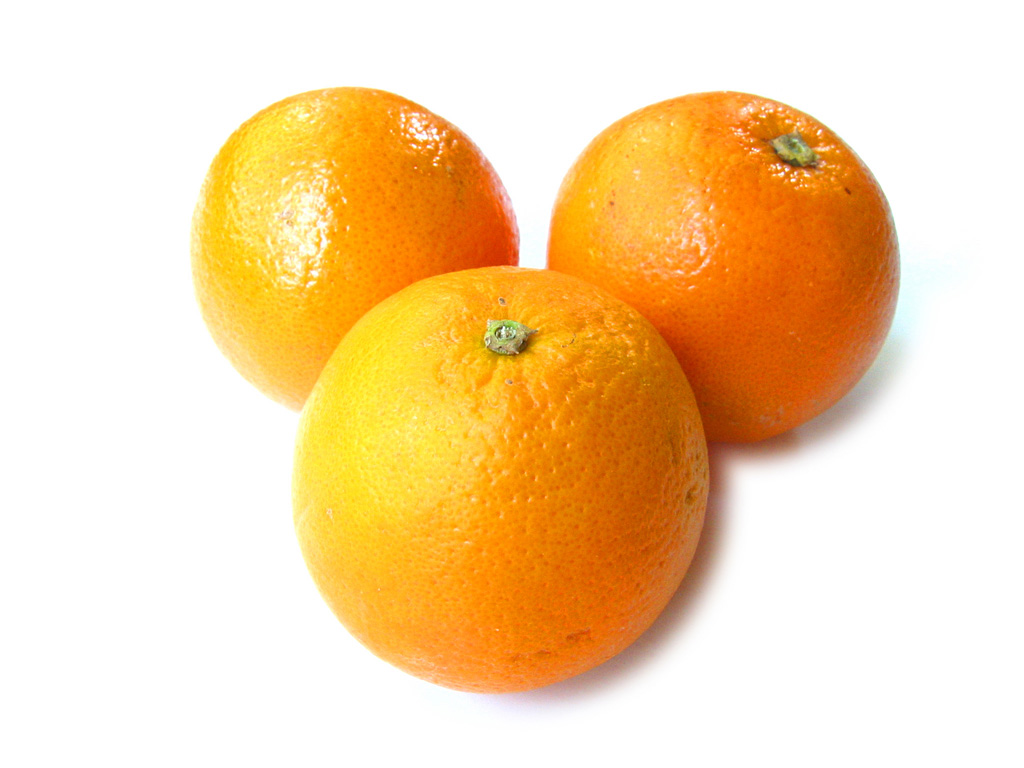

She asked if she could return to her stateroom for something and was given just three minutes. In her stateroom she ignored her own jewelry, and instead grabbed three oranges. Then she quickly returned to her place in the boat.

Just hours earlier it would have been ludicrous to think she would have accepted a crate of oranges in exchange for even one small diamond, but circumstances had suddenly transformed all the values aboard the ship. The emergency had clarified her priorities.

Too Often We Learn Too Late What is Really Important

Gary Redding tells this story about Senator Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts. In January 1984 he announced that he would retire from the U.S. Senate and not seek reelection. Tsongas was a rising political star. He was a strong favorite to be reelected, and had even been mentioned as a potential future candidate for the Presidency or Vice Presidency of the United States.

A few weeks before his announcement, Tsongas had learned he had a form of lymphatic cancer which could not be cured but could be treated. In all likelihood, it would not greatly affect his physical abilities or life expectancy. The illness did not force Tsongas out of the Senate, but it did force him to face the reality of his own mortality. He would not be able to do everything he might want to do. So what were the things he really wanted to do in the time he had?

He decided that what he wanted most in life, what he would not give up if he could not have everything, was being with his family and watching his children grow up. He would rather do that than shape the nation’s law or get his name in the history book.

Shortly after his decision was announced, a friend wrote a note to congratulate Tsongas on having his priorities straight. The note read: “Nobody on his deathbed ever said, ‘I Wish I had spent more time on my business.’”